Fox Talbot and the Salt Print Process

There is currently an excellent exhibition at the Tate Britain in London called Salt and Silver that I would recommend to anybody with an interest in the early history of photography. The exhibition is about the history of the salt print process discovered and refined by William Henry Fox Talbot in the 1800s. It contains a selection of prints from early photographers showing how printing techniques became more popular and improved. I took some notes at the exhibition for some follow-up research and one of the referenced texts was a book that was published by Talbot himself called The Pencil of Nature. It was published in six installments between 1844 and 1846 and is an account of his path and motivations during his discovery and cultivation of the calotype printing process. It’s available for free on Project Gutenberg and it’s not very long so it’s easy to install on a Kindle or mobile device and read on the way to work.

Talbot was a British inventor born in 1800 who made major contributions to the development of photography as an art. In The Pencil of Nature he describes how he came to think about the possibility of a photographic reproduction. In October 1833 Talbot visited Lake Como in Italy. As anybody on holiday in modern times might, he wanted to record what he saw in this beautiful location. The best available tools at the time were artistic sketches made by eye or using a Camera Lucida as a drawing aid. Sketches and paintings were often not very scientific and required a degree of skill and artistry for a faithful reproduction of the scene. The Camera Lucida projected the image onto the paper in a form of double exposure, which meant that observers could simply trace the important lines of geometry in the scene and achieve a good likeness of perspective and size. Talbot used the camera lucida to make the sketch shown here (I’m not inlining it as I haven’t asked for permission):

In the book he describes his extreme disappointment with the result:

For when the eye was removed from the prism – in which all looked beautiful – I found that the faithless pencil had only left traces on the paper melancholy to behold.

– William Henry Fox Talbot, The Pencil of Nature

Talbot spent time pondering whether or not he could improve the process by making it automatic, removing the low fidelity human element from the image recording process. He knew that certain chemical salts were sensitive to light. He made some experiments mixing silver nitrate and sodium chloride to produce silver chloride (neither ingredient is light sensitive on its own, and silver nitrate is good at displacing other metals from salts, so it’s simple to produce the light sensitive combination), silver iodide, and silver bromide and then using them for print making. He varied the relative quantity of silver nitrate and salt and by 1834 had found a way of producing a photographic contact print that was satisfactory. He discovered that a high quantity of salt in the original mixing process would thoroughly arrest development, so subsequently he used a salt solution as a fixing wash to ensure that no further development occurred after the initial exposure.

This process, of the formation of a subchloride by the use of a very weak solution of salt, having been discovered in the spring of 1834, no difficulty was found in obtaining distinct and very pleasing images of such things as leaves, lace, and other flat objects of complicated forms and outlines, by exposing them to the light of the sun.

The paper being well dried, the leaves, etc. were spread upon it, and covered with a glass pressed down tightly, and then placed in the sunshine; and when the paper grew dark, the whole was carried into the shade, and the objects being removed from off the paper, were found to have left their images very perfectly and beautifully impressed or delineated upon it.

When used as the photographic medium with a camera obscura however, the result was unsatisfactory and took a very long time – too long to make it feasible and comparable to sketches. After a long exposure time (he quoted two hours for one exposure) the outlines of buildings and trees could be seen but the details in foliage and brickwork could not.

The next improvement to the process came through the application of multiple coats of alternating silver and salt. He would coat the silver, let the paper dry, coat the salt, and then repeat the process a few times. He also found that by using the paper inside the camera when it was still wet he could reduce the exposure time with a camera obscura to around 10 minutes. The next problem was that the prints were very small as the paper had to fit inside the camera and that the preparation took a long time before a piece of paper could be exposed.

In 1839 Louis Daguerre published his independent findings in the practice of photographic image making before Talbot had published anything. Daguerre’s announcement of the Daguerrotype process did not initially describe how it worked, but simply stated that it was possible. Talbot notes that he had been considering collating his notes and writings and publishing them to the Royal Society at the end of 1838, but he got sidetracked with chronicling another scientific observation that he had made whereby he could produce products of different colours by exposing thin leafs of silver with drops of iodide on them through colourer filters.

[…] a most unexpected phenomenon occurred when the silver plate was brought into the light by placing it near a window. For then the coloured rings shortly began to change their colours, and assumed other and quite unusual tints, such as are never seen in the “colours of thin plates.” For instance, the part of the silver plate which at first shone with a pale yellow colour, was changed to a dark olive green when brought into the daylight.

Talbot remarked that the discoveries by Daguerre were remarkable but was upset that he was unable to announce the discovery of the photographic art to the world.

Such was the progress which I had made in this inquiry at the close of the year 1838, when an event occurred in the scientific world, which in some degree frustrated the hope with which I had pursued, during nearly five years, this long and complicated, but interesting series of experiments—the hope, namely, of being the first to announce to the world the existence of the New Art—which has been since named Photography.

Having heard Daguerre’s announcement, Talbot began to refine his process. He shortened his exposure times and developed salt printing as a way of converting his paper negatives to a positive – producing the first negative-positive process. The paper would be coated with wax to improve its transparency and then contact printed. Daguerrotypes were superior to Talbot’s calotypes in several ways. They had a greater tonal range and preserved much more detail but it was impossible to reproduce the images. Each Daguerrotype is a one of a kind. If you see one, that piece of metal was actually inside the camera when the picture was taken. In contrast, Calotype negatives made it easy to produce multiple copies although the quality was influenced by the size of the fibers in the original paper negative. Talbot announced his method in 1841 and but decided to patent it. Daguerre on the other hand made his method available without restriction as a gift to the world. This patenting is seen as a mistake by many people as it slowed growth in the calotype’s uptake and it caused an additional cost for users.

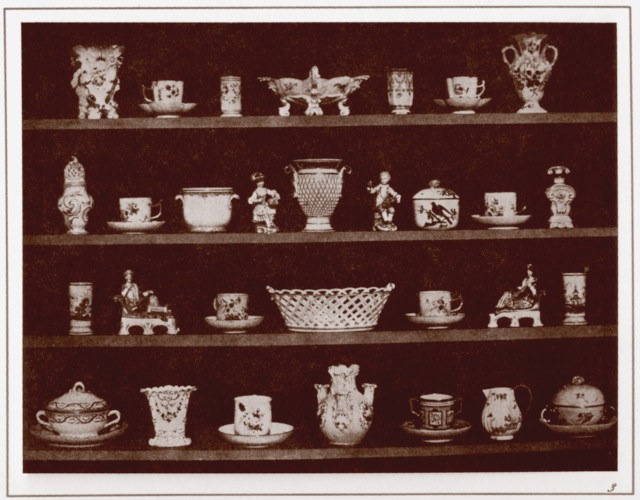

In The Pencil of Nature, Talbot provides several images showing the properties of his technique and suggests certain uses. In an image entitled ‘Plate III. Articles Of China’ (above) he suggests (in a tone that suggests humour to me) that these prints could be used as proof of ownership of items in a court case against a thief:

And should a thief afterwards purloin the treasures—if the mute testimony of the picture were to be produced against him in court—it would certainly be evidence of a novel kind; but what the judge and jury might say to it, is a matter which I leave to the speculation of those who possess legal acumen.

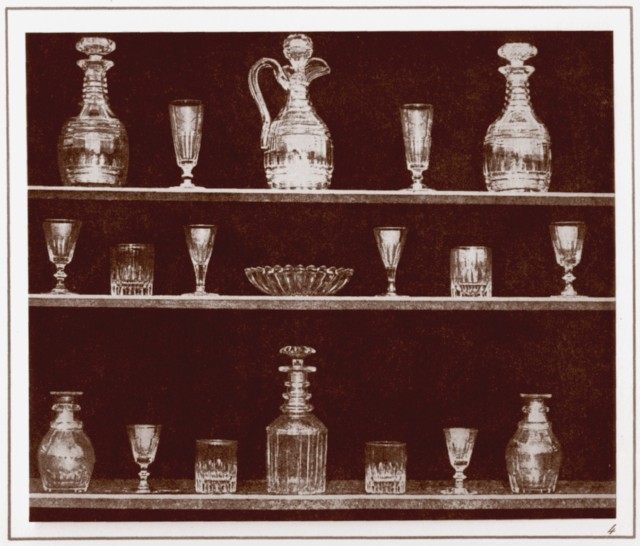

In ‘Plate IV. Articles Of Glass’, Talbot describes his finding that the sensitivity of the paper negative varies depending on the colour of the light it is receiving. He notes that blue hues affect the paper almost as rapidly as white hues, but “on the contrary, green hues act very feebly”.

Talbot also describes what might be the earliest description of using a photographic reflector to enhance the available light and reduce shadow contrast when taking a picture.

[…] it is a good plan to hold a white cloth on one side of the statue at a little distance to reflect back the sun’s rays and cause a faint illumination of the parts which would otherwise be lost in shadow

He also notes that hen light is split by a prism and the image recorded on paper, the calotype negative records exposure from parts of the spectrum beyond the visible red – ultraviolet light.

There’s an excellent description of how his negatives work as well:

The ordinary effect of light upon white sensitive paper is to blacken it. If therefore any object, as a leaf for instance, be laid upon the paper, this, by intercepting the action of the light, preserves the whiteness of the paper beneath it, and accordingly when it is removed there appears the form or shadow of the leaf marked out in white upon the blackened paper; and since shadows are usually dark, and this is the reverse, it is called in the language of photography a negative image.

‘Plate XX. Lace’ is the first example he provides of such a negative:

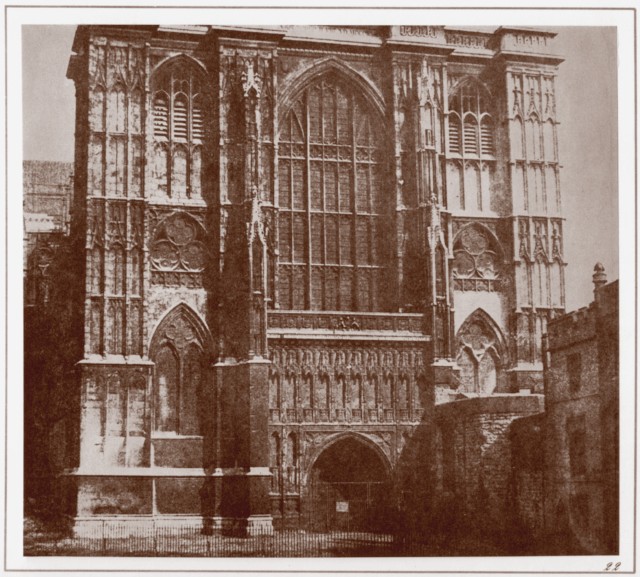

Each of the plates provided has a short description. My favourite is the photograph of Westminster Abbey from plate XXII:

Being a resident of London, I find the description quite funny:

The stately edifices of the British Metropolis too frequently assume from the influence of our smoky atmosphere such a swarthy hue as wholly to obliterate the natural appearance of the stone of which they are constructed. This sooty covering destroys all harmony of colour, and leaves only the grandeur of form and proportions.

I thoroughly recommend that anybody interested in early photographic processes who is living in or visiting London should visit the exhibition. I have several pages of notes on follow-up research and discovering Talbot’s book was just one of the excellent things about the collection.